Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Liberalism as a Way of Life by Alexandre Levebvre

We search for freedom this issue, as Kevin Currie points out the many varieties of liberalism.

“That’s because you’re a liberal!” my self-identified ‘progressive’ colleague said to me with slight contempt. We were talking about the importance of the right to conscience even when it means the right to hold noxious – maybe racist or sexist – views. As a liberal, I loathe sexism and racism just as she does; but equally, as a liberal, I loathe putting moral restrictions on what people may believe or enact in their private lives. Yet to my progressive colleague, these views are antique and liberalism is akin to not taking a stand on much of anything, thus letting individual rights run roughshod over social justice.

She’s not alone. Liberalism is encountering pretty serious resistance these days. Liberals expect it from the conservative right, of course, but it’s now also coming from the progressive left, as my colleague exemplifies. Books are being written with titles like After Liberalism and Why Liberalism Failed. Yikes!

Not so fast, says Alexandre Levebvre in his new book Liberalism as a Way of Life (2024). The title describes its contents perfectly. The book celebrates liberalism not just as a type of political order centered around individual freedom, but as an attitude towards the world. Moreover, Lefebvre suggests that liberalism has been so successful in the Western world that it is now a primary source of how we come to understand our situations. For instance, if you’re suspicious when people trade their individuality for group identity; if you presume opportunity inequality to be a bad thing; or if you believe that everyone should have a fair shot in life regardless of their background, then you are a liberal – maybe even without realizing it. As Levebvre would say, you’re a fish so surrounded by liberal water that you don’t realize how wet you are.

This argument – that we live in such a liberal culture that we often forget just how liberal we are – forms Section 1 of the book. Lefebvre uses great examples here, like the sitcom Parks and Recreation, which centers around a team trying to provide a public good to a community who often puts more value on individual rights – a liberal theme through and through. Or there’s the emerging ethos in comedy that morally speaking, one can’t ‘punch down’ – meaning, get laughs by poking fun of, or using slurs against, members of vulnerable groups. This is a liberal way to think. And for my progressive colleague, I’d add another example: Critical Race Theory, which is often incorrectly derided as ‘illiberal’. However, it is (almost invisibly) premised on liberal ideas: a hatred of unjust (white) privileges and (black) disadvantage; and an individualism which recognizes that race labels (‘white’, ‘black’) are social constructs that get in the way of people being treated as individuals. Critical Race Theory may reach so-called ‘progressive’ conclusions, but I couldn’t imagine it finding any purchase in a society that wasn’t sympathetic to liberal ideals.

Rawlsian & Other Liberalisms

Now we come to Sections II and III of the book, where it disappoints to a degree.

Section II is entirely about the liberalism of John Rawls. Rawls changed the game in political philosophy and indeed liberalism with his now classic 1971 book A Theory of Justice. In it he argued for a type of welfare-state liberalism that respected individual rights for all, but justified inequality only in those cases where it worked to the benefit of the least well-off. For Rawls, this is the type of society we would choose if we set society’s rules from behind a ‘veil of ignorance’, meaning, without any knowledge of who we would be or what role we would occupy in the society we were creating. Put differently, these are the principles that Rawls thought would ensure fairness and decency.

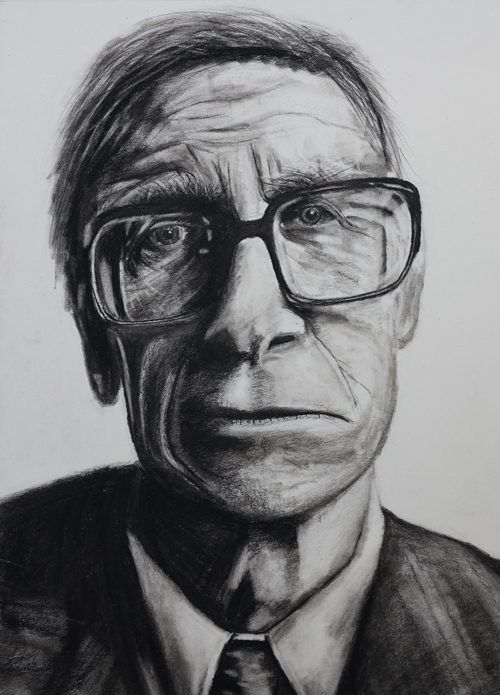

A different kind of liberal: Robert Nozick

Rawlsian liberalism is the kind of liberalism Lefebvre thinks most of us swim in. And he’s sort of right. If you live in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, or one of countless other liberal places, then you live in and were educated into a society that respects individual rights while trying to make sure that the least-well-off are cared for. My big problem with this section (and as we’ll see, Section III) is that Lefebvre talks as if Rawlsian liberalism is the only decent sort of liberalism there is. However, three years after Rawls wrote his surprise bestseller, fellow philosopher Robert Nozick (who had the office next to him) wrote an equally successful response to him called Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974). This advocated a much more minimal liberalism, promoting free markets over a Rawlsian welfare state. Any college political philosophy course that discusses Rawls pretty much has to discuss Nozick too. But there are zero mentions of Nozick in this book.

In fact, there are many flavors of liberalism: pluralistic liberalism (Isaiah Berlin); agonistic liberalism (William Connolly); more socialistic styles of liberalism (G.A. Cohen); and ‘classical’ or libertarian liberalism (F.A. Hayek), just to name a few. While we shouldn’t expect Lefebvre to defend Rawls against all liberal competitors, those who read Lefebvre’s book as an intro to liberalism could get the false impression that Rawls is the only true liberal.

Principles in Practice

Because Lefebvre sees liberalism a way of life rather than ‘just’ a politics, Section III recommends three ‘practices’ that liberals can cultivate in their daily lives. Just as religious people have certain rituals that help them live out their beliefs, Lefebvre thinks liberals should cultivate their liberalism by engaging in regular liberal practices. These practices he also gets from Rawls.

The first practice is to imagine human society from behind the Rawlsian veil of ignorance, where we appraise society’s rules with an eye toward whether we’d endorse them if we didn’t know what our place in that society is or would be. The second practice is ‘reflexive equilibrium’, another Rawlsian term, meaning, we always seek to interrogate our beliefs with an eye toward rooting out contradictions and striving for internal consistency. Third is the Rawlsian practice of ‘public reason’. This means framing our views in terms that others could understand, and accept; and the reverse: understanding others’ views by imaginatively couching them in terms we ourselves could accept. Lefebvre argues that these three practices will increase our liberal sense of justice, coherence, and tolerance respectively.

John Rawls by Athamos Stradis 2025

You may have guessed that while I’m a liberal, I do not consider myself a Rawlsian. (For anyone interested, I’m drawn both to the pluralistic liberalism of Isaiah Berlin and the agonistic liberalism of William Connolly). Likely because of that, I find Section III only mildly compelling. All three exercises are interesting, and I think they can add to our liberal sensibilities. But they are also limited, in ways most evident to non-Rawlsians.

Let’s start with the third practice, ‘public reason’. Remember, the claim is that an ability to tolerate and even rejoice in difference can come from trying to understand others’ views in terms that might be more compelling to us. I did this above with Critical Race Theory. If a liberal decries Critical Race scholarship as ‘illiberal’, they will be less able to open-mindedly examine it; but if they frame it in a more liberal way – for instance, “Ah, it’s saying that race leads to unearned privileges and oppressions, both of which we’re against!” – then they’re better able to understand and appreciate it (even if they don’t endorse it). Practicing this type of public reason, Lefebvre argues, increases tolerance.

Okay, fine. But it can also limit tolerance, insofar as it implies that we can or should only tolerate things that can be put into terms that we can understand. Yet maybe a more expansive and virtuous type of tolerance is the skeptical kind: the kind that recognizes that because our understanding is limited, we can and should also tolerate certain things despite not being able to understand them.

Or take practice two – the idea that we should always strive for ‘reflexive equilibrium’ , meaning, aspire to root out contradictions in our beliefs. Lefebvre argues that doing this will lead us to increasingly thoughtful and good beliefs. But I don’t buy it. When we interrogate and reform our beliefs – which we should do, I agree! – as often as not we find that the world contains or elicits a plurality of values: that the world, and the rules we must use to navigate it, aren’t as simple as we thought. So, far from rooting out contradiction, I’d argue that sometimes we should embrace contradiction, and consider that maybe no consistent set of rules can be found for navigating as complex a world as ours. I’d even add that standing in awe before contradiction and ambivalence may be as deeply important a practice for liberals as trying to root them out.

To my self-proclaimed progressive colleague, I proudly own that I am a liberal. And to agree with Lefebvre’s point, I think she might be more liberal than she realizes. But I’d hesitate to give her this book as a way to back up that claim. Many liberals are in effect Rawlsians, but many are not. While this book is interesting, especially in how it frames liberalism as a way of life more than a politics, it is of limited value to those not already Rawlsian.

© Kevin Currie 2025

Kevin Currie is a Teaching Professor in East Carolina University’s College of Education. He generally focuses on the philosophy and history of education, and is the author of the book Education in the Marketplace (Palgrave MacMillan).

• Liberalism as a Way of Life, by Alexandre Levebvre, Princeton UP, 2024, £12.99 pb, 304 pages