Your complimentary articles

You’ve read three of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Rope

Les Jones has a Nietzschean take on a Hitchcock thriller.

It’s shrouded by darkness, but it is there: the tear that wells in the eye, then slowly rolls down the cheek, silently drops and splashes into the already soggy bag of popcorn on the cinema-goer’s knee.

Cinema can often create this ‘sadness’ effect on people – as well as elation, excitement, or magic. But why? This is known in philosophy as the paradox of fiction: how can we experience genuine, sometimes powerful, emotions towards characters that we know perfectly well are not real?

Often such emotions arise from movie directors’ deliberate cultivation of their audience’s propensity for sympathy or empathy. This raises questions about manipulation or emancipation, and about the ethics of storytelling. As that tear in the eye tells us, film is far from passive. Fundamental feelings are unleashed and perhaps for certain people this is the only situation in which particular passions are unleashed. If we can engage with such visceral feelings we may inculcate notions of fairness, empathy, and other aspects of morality into viewers. Wouldn’t that be good? Or would it be kind of sneaky? Let’s consider a movie that in the opinion of many has much to contribute to film as morality.

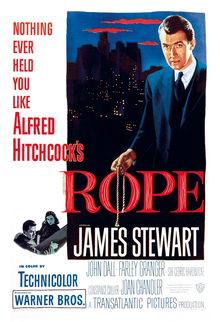

Film images © Warner Bros 1948

Rope was a 1948 Alfred Hitchcock film, famed among film buffs for having been shot in a very small number of continuous takes. Its central characters are two clever and assured young men, Brandon and Philip. They have been taught about Nietzsche’s philosophy, and it seems to them to dovetail with their own views of themselves as being superior to the common crowd. In other words, they choose ideas that support their own predilections.

The Übermensch or ‘Overman’ (or ‘superman’) is an important aspect of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy. Nietzsche’s social philosophy has much to say about leaving the accepted order behind and moving onto a new social, moral and economic plane through the superior man who makes his own values. To get a flavour of a small part of these challenging ideas, we need only turn to some of Nietzsche’s notions on religion. Nietzsche thinks that Christianity stands opposed to every spirit that has turned out well: “It utters a curse against the spirit, against the superbia of the healthy spirit… Sickness is of the essence of Christianity” (The Antichrist, section 52, 1895). So among other things, the Übermensch is about building an alternative to Christian morality.

Brandon is infatuated by the notion of the Übermensch as it meshes with his own notions of himself, but his interpretation of this concept is … problematic. The young men’s tutor Rupert explained the idea of the Übermensch to them, but Brandon seems to have twisted it into what many would regard as a grotesque caricature. For him it implies the right of the Übermensch to murder lesser mortals, if they can justify the murder by the cunning with which it was carried out.

Accordingly, the film opens with Brandon and Phillip murdering their former friend David. Brandon is exhilarated by the murder, Phillip less so. Then a dinner party is organised by Brandon, assisted by Phillip. David’s dead body is hidden in an unlocked trunk, which is set provocatively at the centre of the party. Risky? Surprisingly, this is part of Brandon’s plan to prove his superior intellect. His infatuation with Nietzsche’s philosophy is such that he seems completely consumed by it. It is unclear whether he has considered the roots of Übermensch ideas in Nietzsche’s thought, in the idea that right and wrong depend on the power structures in society, and that religion – Christianity in particular – corrupts the attention in that it turns minds away from what can be achieved in life and puts the focus on an afterlife where all will be well. It would seem that Brandon’s fascination with Übermensch philosophy is mainly concerned with his own narcissism.

Those invited to the party are a testament to Brandon’s view of his superiority: David’s best friend Ken Lawrence; David’s fiancée Janet, who is also Ken’s ex-girlfriend; David’s father Mr Kentley; and Rupert Cadell, Brandon and Phillip’s tutor – the man who introduced them to Nietzsche and whose intellect they recognise. The rest are just the kind of conventional ‘normal’ people that Brandon would kick against. Brandon’s notion of the Übermensch demands that he spit in the eye of social conformity. Indeed, his relationship with Phillip has gay connotations – and this in 1948 when such things were decidedly frowned upon. It may also occur to the audience that as well as kicking against ‘clearly defined identities and relationships’, Brandon and Phillip may be hitting at a sexuality that they see as oppressive and regressive, which is determined to see their own sexuality as in some way deviating from a norm. (For more on this, see for example Thomas J. Roach’s paper ‘Murderous Friends’, in the Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 2012)

Brandon, in a typically provocative and perhaps sickening gesture, ties some books together with the rope used to murder David. This suggests his contempt for contemporary mores, his confidence in his own Übermensch qualities, and a complete lack of empathy with others at the party (again, David’s father and fiancée are there). His utter contempt for those he sees as inferior is reflected in his comment to Phillip after the murder: “Good Americans usually die young on the battlefield. Well, the Davids of this world merely occupy space, which is why he was the perfect victim for the perfect murder.” Needless to say, many in the audience would be repelled by such sentiments. Those devoted to the Christian golden rule of ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’ would be horrified, but so would those who recognise Kant’s Categorical Imperative as a rule to live by, who would see Brandon’s actions as a green light for anarchy. Nor would Nietzsche himself have been likely to approve Brandon’s action, given his own views on the ‘will to power’, first discussed in The Gay Science (1882). There he argues that causing pain is generally less pleasant than showing kindness, and suggests that cruelty is an inferior option to kindness because it is the very antithesis of what one is trying to exert: it is the option that shows lack of power.

Nietzsche by Woodrow Cowher

The more philosophical members of the audience may be troubled not only by Brandon’s lack of compassion, but also by his apparent lack of knowledge of meta-ethical theories that contradict those of Nietzsche. I’m thinking particularly of the view that the essence of man is as a social being, so it is natural for humans to act in prosocial ways, rather than from selfish individualism. Humans are also natural language users. The questioning viewer might reflect that the tool for thinking is language, which, by its very nature, is governed by rules. However, one cannot obey rules in a private or individualistic capacity, for then merely thinking one was obeying a rule would be enough to be obeying it. Therefore, rule following is essentially a social phenomenon. Its very existence depends on good social interaction. Any cinema-goer familiar with such ideas would, to be sure, be very sceptical of Brandon’s intellectual bedrock. One may also reflect on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, which states, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

The audience of course have privileged knowledge of events. Still, reflecting on the cruelty of the arrogant Brandon, they may wonder what could possibly drive such behaviour. Although they may be inclined to suspect flaws in Nietzsche’s philosophy or in Rupert’s approach to teaching it, the rest of his students haven’t turned out like Brandon – not even the tortured and remorseful Phillip. This in turn suggests that Rupert’s emphasis on certain parts of Nietzschean philosophy may just have given Brandon, in his mind, some justification for doing whatever he wanted to do anyway. The denouement of the film sees Rupert emerge as possessing some integrity, whereas Brandon’s imperious attitude begins to fall apart. His sarcasm disappears as his identity as a cruel manipulator and murderer is exposed. The moral of the story? Caution is the watchword when explaining difficult ideas to impressionable people.

© Les Jones 2026

Les Jones is a retired educational professional. He taught in schools and colleges, and has been a department head. He has also worked for exam boards as an examiner and senior examiner for GCE, GCSE and A-Level.