Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

What Women?

Marcia Yudkin remembers almost choking at Cornell.

“We should look upon the female state as having as it were a deformity, though one which occurs in the ordinary course of nature.”

– Aristotle, The Generation of Animals, 4th century BCE

When I was a student there in the Seventies, every other Monday evening the Cornell University Philosophy Department convened in a tournament called ‘Discussion Club’. The event began promptly at 8 o’clock. The night’s presenter would gallop out onto the field for no more than twenty minutes, kicking up dust with a position on so-and-so’s objections to whoever’s theory of such-and-such. Then a challenger trotted out for ten minutes, letting his banners fly as he charged the lead rider with cunning thrusts of reasoning. Then anyone present could jump in with prances or parries, lunging with their logical lances or just strutting their smarts. At the close of action at 10 o’clock, rarely was anyone declared a victor or some truth acclaimed by the crowd. But scored points mattered, and carried over in the minds of all the regulars, bout after bout.

At the door of the classroom where the joust took place, some junior fighter had been delegated to hand out cigars, on which even men who did not normally smoke puffed while watching and participating. Alice, Joanne, and I – the three women in the first-year graduate student class – would sit at the back, cranking open windows and waving as much smoke out of the room as we could.

Attending this event month after month, we women choked in more ways than one.

Coming To Cornell

“If a man behave with cowardice on one occasion, a contrary conduct reinstates him in his character. But by what action can a woman, whose behavior has once been dissolute, be able to assure us, that she has formed better resolutions, and has self-command enough to carry them into execution?”

– David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, 1751

For graduate students attendance at Discussion Club was required. One or two tenured professors habitually skipped it, but turnout swelled when a guest speaker from Princeton, MIT, or UCLA was on the bill. By participating, the faculty practiced their skills at the highest level, showed off, and maintained the national and international reputation of the department. By watching and listening, we philosophers-in-training learned what counted in the discipline and how we would need to perform to receive our PhDs.

When I was an undergrad at Brown, I’d boogied philosophy with my professors, taking ideas out for a spin and creatively dancing through them step by step. I could handle nitpicky analysis like a pro; but I also liked to inject my papers with an imaginative angle. But at Cornell I soon realized that the department as a whole, not just professors I took courses with, would be evaluating me. The department saw its duty as turning out new versions of themselves, including the proper habits and attitudes. Yet I didn’t want to turn into a jouster, I wanted to remain a playful questioner. And I sensed my challenge had everything to do with the gender mix in the department.

In 1974, when I arrived at Cornell for my graduate studies, its philosophy department had no women professors. Coming from Brown, where the philosophy department also included no women, I never thought about this. Even in high school most of my teachers had been men, although just one meanly preached that women couldn’t do hard thinking. Nor had I witnessed discrimination against women students. And though I’d studied a lot about women’s historically second-class status, I saw improvements. Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth all now admitted women undergraduates. Congress had approved the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution, and sent it to the states for ratification. Women had achieved economic rights and advanced in sports and the professions. So the jousting at Cornell jolted me. Alice, a Stanford grad who had a snappy, high-energy style, felt equally unsettled, and we began having lunch together Tuesdays and Thursdays. A sociology grad student named Linda soon joined us. Her acerbic comments about her department helped all three of us develop perspective on the inculcation we were instinctively holding at arm’s length.

Women Within Reason by Melanie Wu

© Melanie Wu 2025. Please visit her instagram: @melaniewu_illu

Collective Observations

“Nature herself has decreed that woman, both for herself and her children, should be at the mercy of man’s judgment.”

– Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, 1762

During our lunchtime study group, Alice, Linda, and I shared observations that bothered us. We groped for concepts that named our experience and shed light on our personal dilemmas. These are some ideas we developed:

• We found the macho professional role models held up for us to imitate repulsive. Cut-throat aggressiveness seemed horribly over the top and wrong in the realm of a search for truth and understanding.

• Professors who agreed with criticisms of their standards for evaluation nevertheless enforced those standards in their grading. Were psychological knives – either external, or inside of them – menacing them in ways they wouldn’t have wanted to admit?

• Emphasis in our courses on ‘methodology’ and ‘rigor’ – that is, on form independent of content – kept disciplinary boundaries strict and narrow. As philosophy professionals in training, we weren’t supposed to care about issues of race, gender, or the meaning of life – only about whether we’d shielded our arguments well enough against counterthrusts.

• As feminists, we choked on the smoke of patriarchal values and customs while the men breathed easily, as supposed ungendered neutral reasoners. As women, we were outsiders in academe, and represented a threat to the towers of male power.

• Although undergrads had permission to explore and innovate, errant grad students got pounded down so that renowned departments could continue to reign near the pinnacle of the ratings.

• We felt confused when accused of being ‘anti-intellectual’ or ‘lightweights’, because we actually revered thinking. But champion jousters guarded their approach by slapping scornful labels on anyone who questioned their sport.

• Was it worthwhile to buckle down and get credentialed within an academic system that ground down creativity and activism?

Chalk vs. Chauvinism

“Women will avoid the wicked not because it is unright, but only because it is ugly… Nothing of duty, nothing of compulsion, nothing of obligation!… They do something only because it pleases them… I hardly believe that the fair sex is capable of principles.”

– Immanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, 1764“Women are capable of education, but they are not made for activities which demand a universal faculty such as the more advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production.”

– G.W.F. Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right, 1820

Simone de Beauvoir 1955

I proceeded to mount a guerrilla campaign within the department. In the faculty lounge, open to graduate students, I commandeered the top right corner of the chalkboard that stretched wall to wall: I headed my communiqué ‘Sexist Quote of the Week’. Without further comment, I copied a sentence or two from one of philosophy’s greats – Aristotle, Hume, Kant, Sartre, Schopenhauer, or still-living luminaries. Some passages poured general contempt on women, others denied women’s ability to think. Still others took ‘male human’ as interchangeable with ‘person’. An extract from the standard logic textbook used across the profession treated women as a joke. And just once, I edited ‘sexist’ to ‘feminist’ in the heading, and posted something by Simone de Beauvoir.

By going into the lounge early or late I updated my posting once a week without anyone catching me at it. Between classes I would amble into the lounge, innocently drink coffee while reading, and prick up my ears – but no one ever commented on the quotes in my presence. I never heard conversation about my missives or speculation about who was the sneak. Yet since the rest of the chalkboard held departmental announcements, all the men had to have read my citations and felt at least a little discomfort.

I openly resisted, too. In two of my classes, I clashed with professors who insisted I toe the line by writing the standardly dry, technical papers. In the first, I wrote a monologue, reasoning through the topic of the course in the voice of a character. This wasn’t just a creative romp: it reflected my conviction that thoughts and ideas emerge from people at a time and place rather than from anywhere and nowhere. Our eminent, Azerbaijan-born teacher, who wore wonky glasses like Mr Magoo, declared this unacceptable. But at a meeting with my ‘committee’ – the three professors responsible for my academic progress – Nick Sturgeon, an ethics specialist, scoffed at his colleague’s rigidity: “A monologue – so what? Plato wrote dialogues, for God’s sake. Hume, Berkeley and Leibniz did too.” So this rebellion didn’t get me thrown out.

A semester later, in a class on the metaphysics of personal identity, I scrutinized the topic by bringing in cases like Alice in Wonderland and Jan Morris, formerly James Morris. The professor told me I’d get a ‘C’ for the course unless I rewrote the paper in the mode of tiny distinctions dancing on the point of a needle. He had a craggy, washed-out face that flashed with anger as he criticized what he said were my crude, irrational, and willful misunderstandings: “You didn’t engage with the philosophical literature. You attacked the weakest formulation of my position and didn’t defend yours,” he snarled.

“Attack, defend, attack, defend. Why does philosophy have to be done that way?” I objected. He shot me a withering look, like I was a babbling idiot. But my study group with Linda and Alice gave me the guts to stand up straight and continue: “I don’t expect you to understand this, but it seems to me that philosophy is a male club, and they’re saying, ‘Sure we’ll let women in as long as they talk like us, act like us, write like us, and think like us’.”

He crossed his arms and glared. “I don’t have anything to say to that,” he responded. But his evaluation of me for the department said I had an atrocious attitude and no future in philosophy.

Unprofessional Professors

“(a) Susan is featherbrained.

(b) Janet is featherbrained.

(c) Some women are featherbrained.

(d) All women are featherbrained.

(e) Only women are featherbrained.

(f) No man is featherbrained.

…

(w) Some dogs like a featherbrained woman.”

E.J. Lemmon, Beginning Logic, 1965, 1978“Representation of the world, like the world itself, is the work of men; they describe it from their own point of view, which they confuse with absolute truth.”

– Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 1949

Other dramas in the department demonstrated perils for women trying to further their education in a male-dominated environment. Joanne, the third woman in our philosophy first-year graduate cohort, who had long platinum locks and a ‘don’t-touch-me’ aura, told me that the department’s nebbishy youngest professor had chased her around a conference table once. My mouth dropped: “Literally?” She nodded: “The same professor had invited me out for coffee my first week at Cornell, then tried to kiss me, but I’d ducked and pointedly kept my distance afterwards.”

Hush-hush rumors abounded. At the end of my first semester, one professor left so suddenly and so unwillingly that he never turned in grades for his students. The department passed everyone. People said the professor had been entwined in a relationship with a female grad student. People also said that another professor, married with kids, had taken on a mousy grad student as a mistress, and she followed him around like a tongue-tied shadow. Joanne claimed that some male graduate students were sleeping with undergraduates and giving them As. “Every day here, I’m forced to think about being a woman,” she complained. As far as we knew, Cornell then had no policies or reporting channels for sexual harassment, which barely had a name at that time.

My own mentor pursued women students too. Just over sixty, he had a ponderous, stop-and-start manner of lecturing while he paced. A friend characterized him as a cross between John Wayne and Gregory Peck. Wearing a near-uniform of baggy jeans, button-down shirt, knit tie, and tweed jacket, he had a gruff voice that to me evoked a lumberjack more than a film star or a college professor. I’d come to Cornell to study with him because of his close friendship with Ludwig Wittgenstein, my intellectual idol. Gossip had it that his wife had thrown him out of the house and then divorced him for fooling around with a student.

In his seminar I got to know a senior philosophy major named Petra, a pretty blonde. In the library, where we chatted during breaks from reading, she confessed that he had once kissed her then laughed uproariously. “A friendly kiss, or…?” I probed.

“On the mouth!” she exclaimed.

Weeks later, Petra seemed to be holding back on something; but she finally spilled that he had written at the end of his feedback on her final paper, “Before you go off to Heidelberg, why don’t you come over for dinner and spend the night?”

“What?” I sputtered. “He wrote that?”

“I could blackmail him!” Petra snapped. But the advance shook her up so much she couldn’t even bring it up with him when she next saw him, she later told me.

The same professor once walked me home after a late-afternoon meeting, and stopped us on a footbridge over a creek, giving me a look I could not interpret. I turned and continued walking and he did, too. I liked and admired him, but in the light of Petra’s intel, I knew I had to send him keep-off signals. Amidst all the smoky obstacles at Cornell, this felt so, so, so unfair.

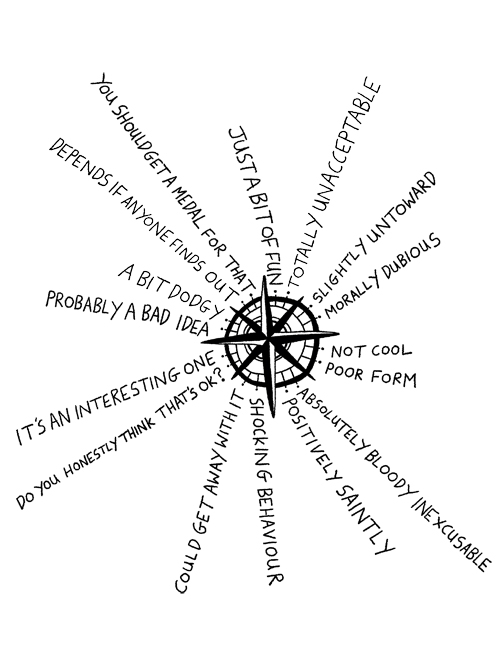

Moral Compass by Owen Savage

© Owen Savage 2025. Please visit oghsavage.substack.com

Progress, Finally

“When those who have the power to name and to socially construct reality choose not to see you or hear you… When someone with the authority of a teacher, say, describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked in the mirror and saw nothing. It takes some strength of soul – and not just individual strength, but collective understanding – to resist this void, this non-being, into which you are thrust, and to stand up, demanding to be seen and heard.”

– Adrienne Rich, ‘Invisibility in Academe’, 1984

My mentor pulled me through the gauntlets of the PhD program without as much suffering as I’d expected from the choking of my first year, and when I eventually described to him my recoil from the Discussion Club, he suggested, “Why don’t you get together with the other graduate students to ask for changes?” So I did that, spearheading a survey that revealed significant patterns of dissatisfaction. And when I related the conflict with the personal-identity professor, he said, “Don’t worry, I won’t let you be bullied.” He stuck up for me effectively enough at the end-of-year departmental heads-together about grad students so that, despite two deeply derogatory reports, again I wasn’t booted out of the program.

In my second year I did well as a teaching assistant, first for an introductory ethics course and then for an interdisciplinary existentialism course, both of which focused on the sort of real-world questions that rarely even got a mention at Discussion Club. I took as many classes outside the department as allowed, including a History of Feminism course. The other grad students elected me to represent them at faculty meetings – a reform agreed to as a result of the survey.

I also discovered fellow rebels in a newly formed national organization called the Society for Women in Philosophy (SWIP). Founded by women five to ten years older than me, SWIP held conferences that analyzed the dynamics that Alice, Linda and I had bemoaned, and proposed sophisticated alternatives to take-no-prisoners intellectual swordsmanship. Partly through contacts at SWIP, I landed a dream job, teaching philosophy and women’s studies at Smith College, where male colleagues were easygoing and reasonable and students largely happy to be taught in a let’s-figure-this-out style. The jousters hadn’t beaten me down, and though I left academe after a few years, I remained mentally alive, still wondering about big questions of truth, knowledge, and who we are when we look in the mirror, at each other, at death, or at the stars.

© Marcia Yudkin 2025

Marcia Yudkin is completing a memoir, Recovering from Wittgenstein.